Simon Yates,

Programmer from Toronto

1997

First production system built

Age 16

Retail role → trusted software

2h → 20m

Repetitive work automated

Still in touch

First manager who trusted me

1997

First production system built

Life as a Maker

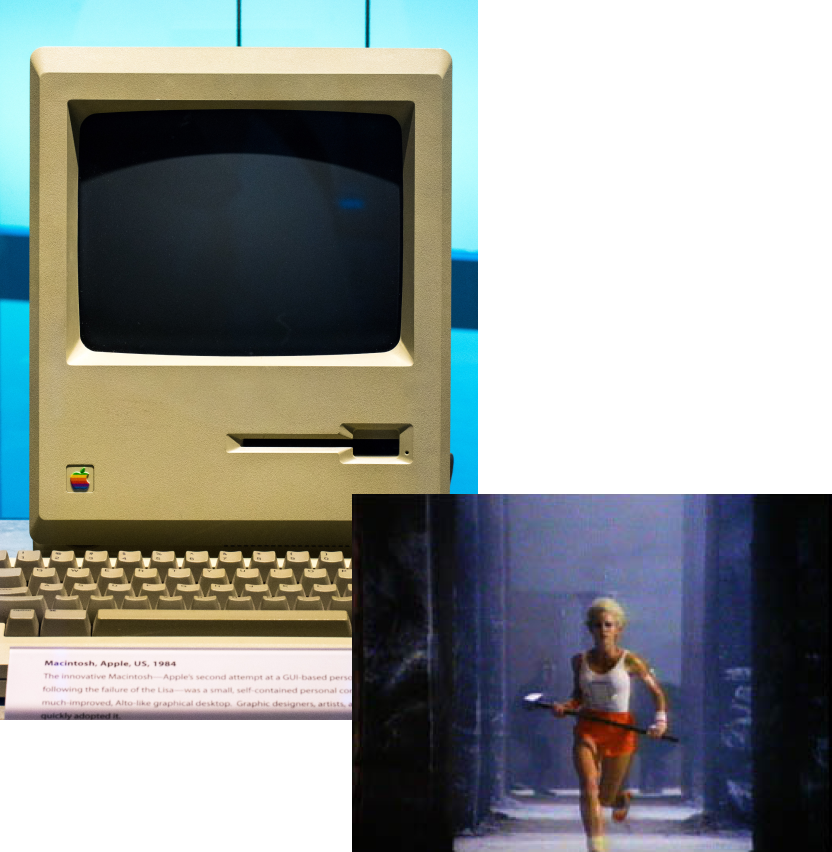

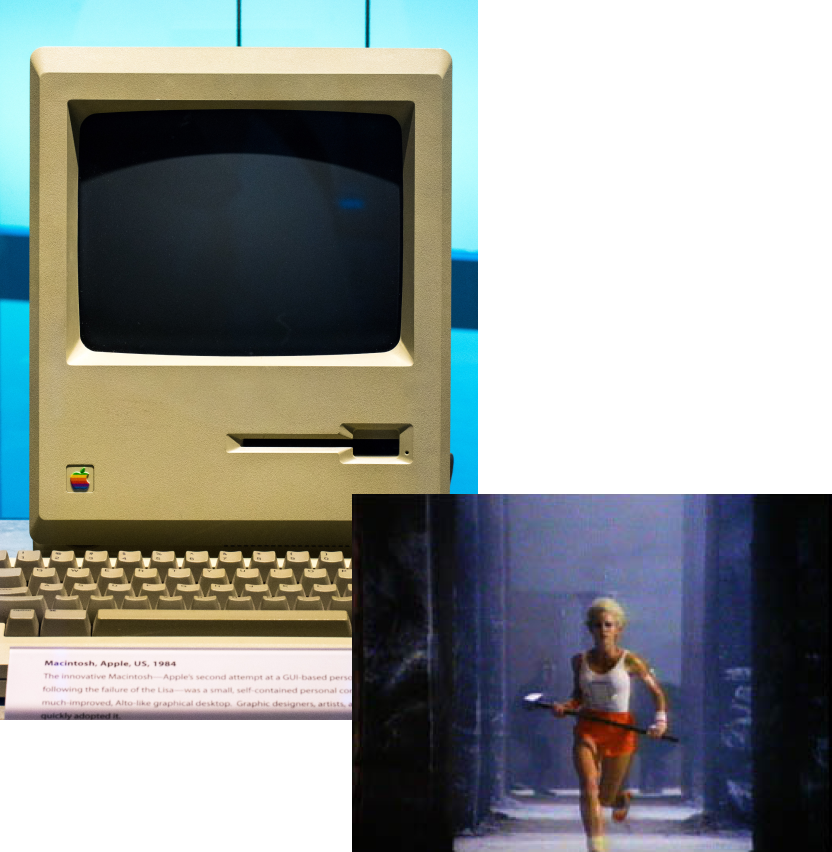

I was 3 when I first used a computer. The year was 1984 and my dad was doing some interior design work for the Canadian headquarters of a computer company out of Silicon Valley. As a courtesy, they let him borrow their newly launched flagship product for a few weeks. It was an Apple Macintosh.

I vividly remember sitting on my dad’s lap and playing with MacPaint, but can’t recall what exactly I drew, it was probably a house – either way, I was hooked!

For the next few years of my childhood, I had dreams of my dad bringing one home, until one day, he did.

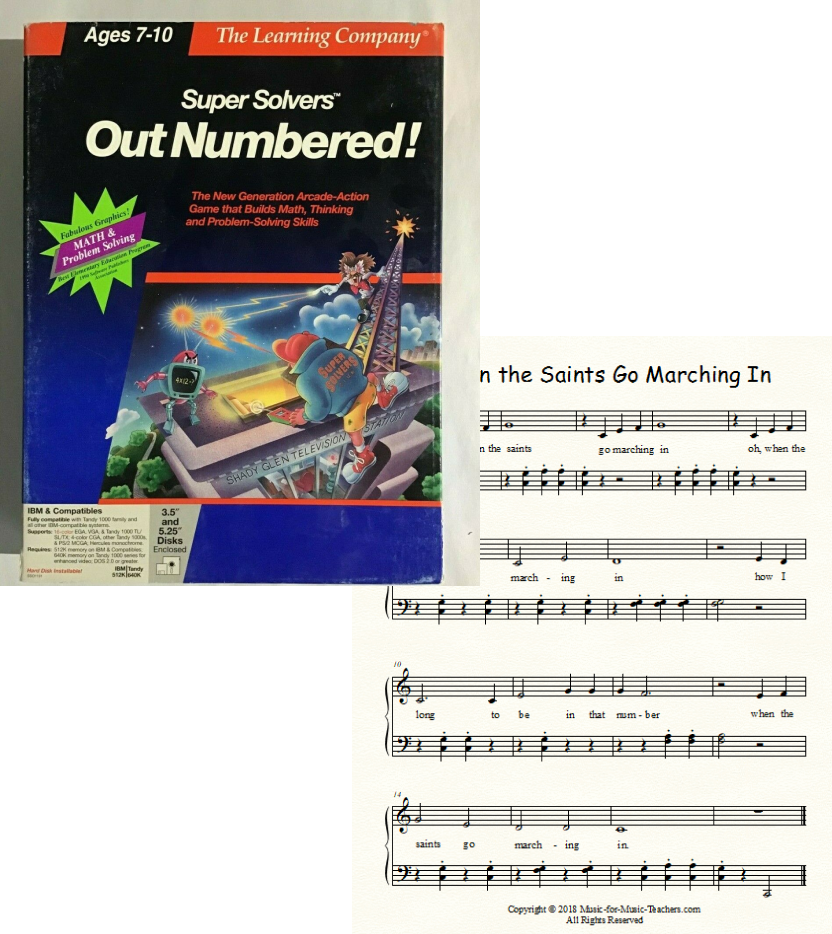

It was an 80386SX with a 40 MB HDD, and (I think) 4 MB of RAM. Pre-installed with DOS 4.01, it came equipped with a SoundBlaster sound card – which was state of the art at the time, and a bunch of educational games from The Learning Company (TLC).

Hello, World!

While TLC’s Super Solvers: Out Numbered! and Challenge of the Ancient Empires! may have kept me busy during summer break, it was this synthesized musical keyboard game that came bundled with the SoundBlaster that I really wanted to play with.

Determined to play music with the computer, I started digging through different files and stacks of owners manuals that were the size of tax law books to try and find any mention of this game.

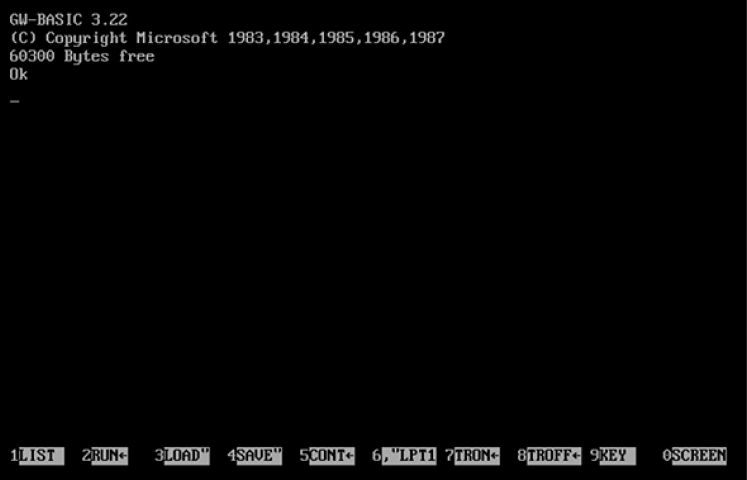

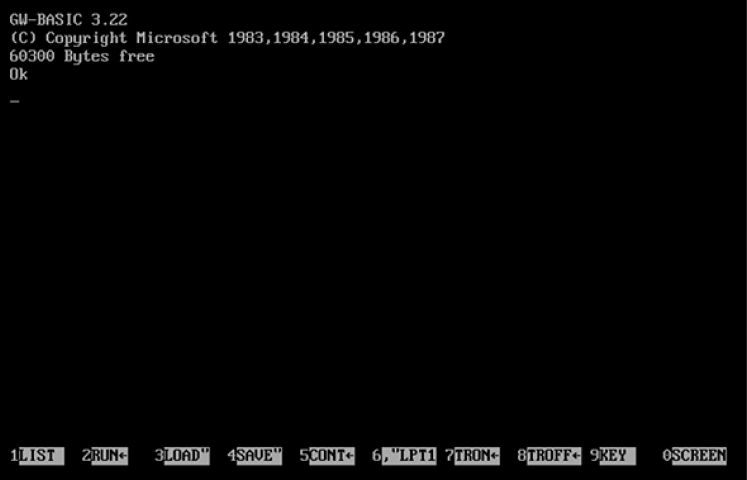

A few days later, I stumbled onto this program called GW BASIC. It didn’t turn my computer keyboard into a MIDI keyboard, but with a few lines of code, I could have the computer produce a sound at a specific frequency for a given duration. It wasn’t exactly what I wanted, but it was fascinating stuff!

I started coding sheet music into the computer and playing it back. My mom was very confused as to why I kept playing When The Saint’s Go Marching In, and other Christmas tunes in the middle of August, but it was the only sheet music I had.

Months later I eventually tracked down the actual program that I was looking for, but by this point, I was too hooked on this programming thing to care anymore. Writing software allowed me to make things and do things that someone hadn’t done before.

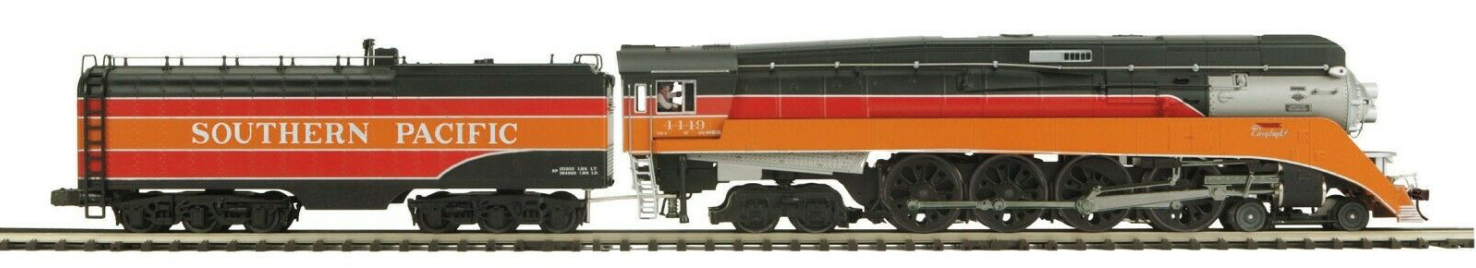

Model trains

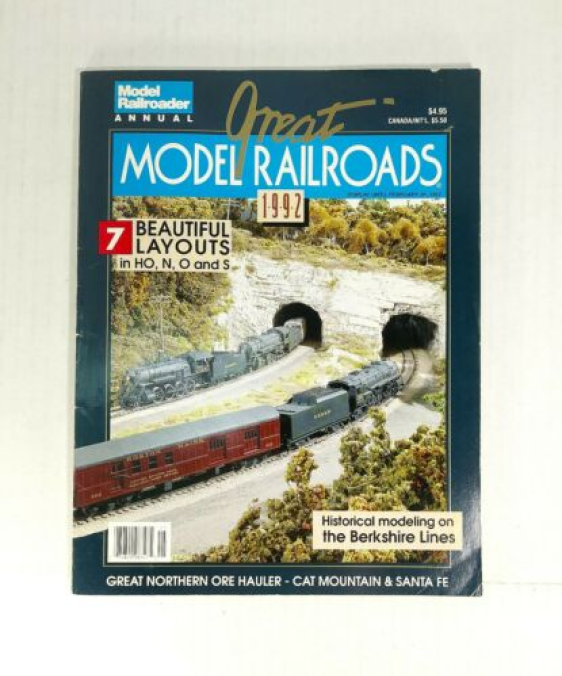

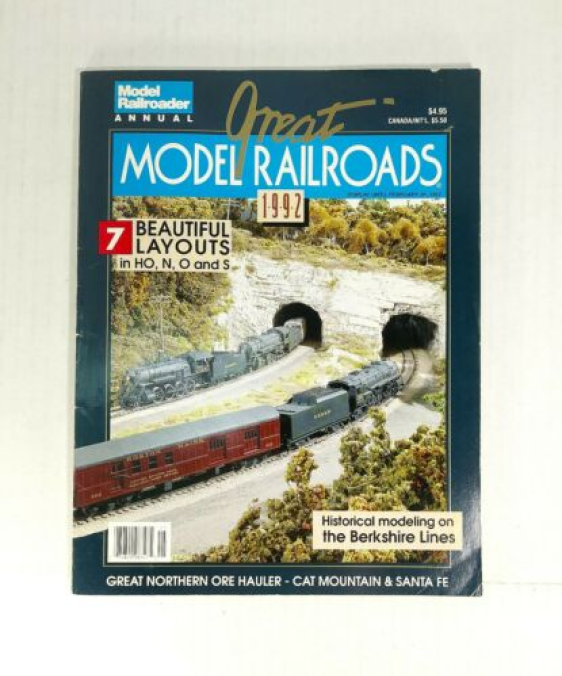

It was around this time that I also started getting into model trains. Model Railroader Magazine would often include snippets of BASIC code that allowed you to control the COM port on your computer, or simulate waybills for imaginary companies that your trains had to make deliveries for. These snippets introduced me to new programming concepts through practical constraints.

As I grew older, making things and solving problems through code became the norm for me. In an unexpected twist, model trains also taught me a great deal about logistical efficiency. A model railroad’s “layout” — the organization of track — is essentially a flowchart built in the physical world.

Computer City (1997)

When I was 16, I worked evenings at a Computer City retail store. After closing, one person would spend nearly two hours rebuilding printed product specification sheets for the computers, monitors, and printers on display.

The process was universally disliked. Specs were often retyped from scratch, layouts varied by printer and display location, and alignment was manual. Errors were common. Time was wasted.

I built a small internal system that stored product specifications in a database and paired them with scanned examples of the store’s approved print templates. Staff could look up a product by SKU, select the appropriate template, and print a correctly aligned spec sheet immediately.

The task dropped from roughly two hours to about twenty minutes.

After that system proved reliable, I extended it to the store’s demo machines. I built a screensaver that displayed the exact specifications of the computer being viewed, alternating with brand-approved slides and store messaging. The screens synchronized across the floor, switching in unison on a timed interval.

This was my first experience building software that people depended on — and my first exposure to real-world constraints: branding rules, consistency requirements, and the responsibility that comes with being trusted to automate someone else’s work.

I’m still in touch with the manager who trusted me with that system.